Sports: Hockey Hall of Fame

Willie O’Ree smashed the National Hockey League’s colour barrier when he was recruited by the Boston Bruins, but the newly inducted Hall-of-Famer gave a young hockey fan from the ‘burbs a big city thrill.

By Rod Mickleburgh

Every now and then, the National Hockey League, even under Gary Bettman, does the right thing. So it was with the recent selection of Willie O’Ree to the Hockey Hall of Fame. O’Ree, 82, was chosen under the hallowed institution’s “builder category,” as the first black to lace ‘em up in the NHL and a long-time ambassador for youth and hockey diversity. In recent years, the honours have piled up for the likeable O’Ree. Banners raised, arenas named, ceremonies, inductions to other, more local halls of fame, and in 2008, the Order of Canada. O’Ree has taken it all in stride, evincing little bitterness over the setbacks and racist taunting he experienced at times during his long hockey career, which lasted until he was 43 years old.

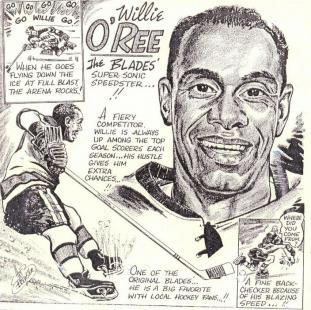

Most of that time was spent in hockey’s minor leagues, a respectable place in those days to earn a few dollars, followed by a summer job to fill out the year’s earnings. Back then, there was nothing pejorative about being “a career minor-leaguer” like O’Ree. And he was a good one. All told, he scored more than 400 goals over 17 seasons, most of them in the Western Hockey League, which included the Vancouver Canucks before they jumped to the NHL in 1970.

Willie O’Ree played only 45 games in the National Hockey League. I was lucky enough to have been at Maple Leaf Gardens for one of them, and I have very clear memories of that magical night. It was my best friend’s birthday, and, baby-boomer parental indifference being what it was, (“go out and play”), we went on our own to the Gardens to watch the Leafs take on the Boston Bruins.

That meant taking the mighty Grey Coach bus from our sweet home town of Newmarket all the way into the big city, about 30 miles distant. This was different from daytime trips with the parents. As a young teen-ager, I remember being awed, and slightly intimidated, by the bright lights and nighttime crowds swirling along Yonge Street, particularly outside the legendary Brown Derby Tavern. But we made our way to the nearby Gardens and plunked down $2 each for standing room tickets. That was the only way to get in, since Leaf games were always sold out.

At the Gardens, you could stand behind the blues, which were best, the greens or the greys at the top of the rink, which were worst. From there, you could barely see the distant players through the haze of cigarette smoke.

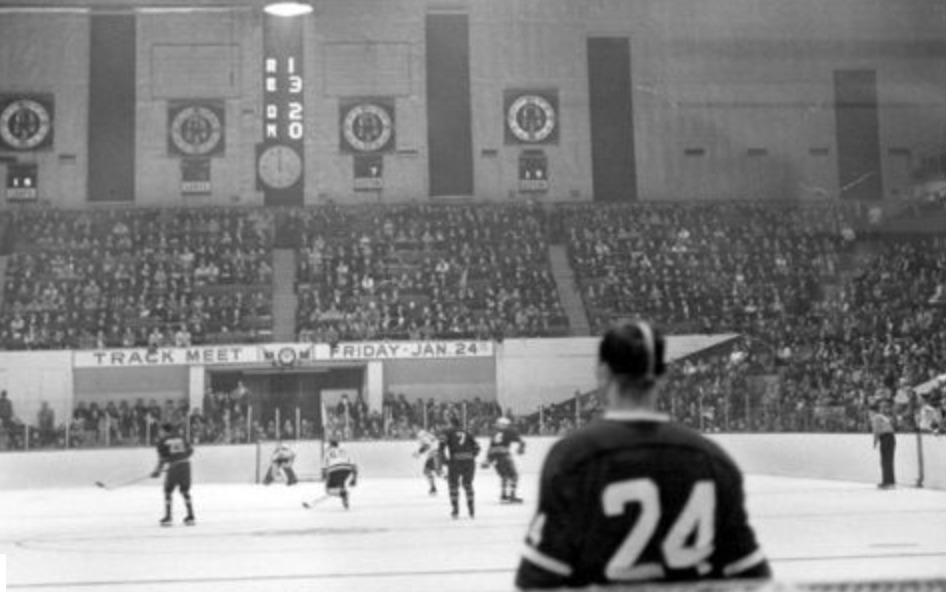

The Old Barn: Maple Leaf Gardens circa 1960 was a classic hockey barn where smoking was part of the experience.

We lined up in the cold with the other standees. An hour before game time, they opened the doors. Everyone rushed through the turnstiles and dashed frantically up the stairs to get a good place. Rather than risk being crowded out behind the blues, we opted for the lesser greens. We may have been the youngest guys there, but we didn’t care. We were at the Gardens seeing the Leafs, our hockey heroes, for a paltry few dollars.

I also knew that Willie O’Ree would be in the lineup for the Bruins. His historic first appearance had been the year before, but he suited up for only two games, before being shunted back to the minors.. Now he’d been called up again, and the Toronto hockey scribes had been writing about O’Ree and what a curiosity he was, a black player in the NHL. So I was curious, myself, to see him, in addition to rooting for the Leafs.

I watched him closely in the warm-ups, noticing what a fast skater he was. He also seemed to have a good, hard shot, based on the noise the puck made cannonading off the boards when he missed the net. It was fun to see him on the ice. But the Bruins were a last-place team, and the game went well for Toronto. As an added bonus, Johnny Bower, my all-time favourite player, made one of the best saves I’ve ever seen, Despite losing his goal stick, Bower hurled himself full length across the net to deny the Bruins a sure goal. The crowd rose as one in a roaring salute to the greatest custodian of the pipes the Leafs ever had.

But back to O’Ree. He didn’t do much in the game. Indeed, during his 45 games in the NHL, he amassed only four goals and 10 assists, which was not enough to keep him in the league beyond the 1960-61 season. Watching him, you could tell he had the speed to be an NHL-er, and he didn’t shy from mix-ups. Yet, he had trouble hitting the net and making those key passes to set up scoring opportunities.

Only much later in life did O’Ree reveal that an early injury had left him virtually blind in his right eye. He had kept it a secret, figuring, probably rightly, that few teams would want him if they knew he had full use of only one eye. No wonder he missed the target so often. I wasn’t the only one to notice it.

Boston teammate Don McKenney recalled a magazine article on O’Ree headlined “King of the Near Miss,” which highlighted the number of his shots that sailed wide. “I’m sure his eye problem was the cause of that because Willie O’Ree was an excellent hockey player in every other regard,” said the skilled McKenney, who occasionally centred a line with O’Ree and Jerry Toppazzini. In the same 2007 interview, McKenney noted exactly what little ol’ teenage me noticed from my perch behind the greens: “He was extremely fast and had a strong shot.”

So not only was O’Ree the first black to play in the NHL, he might have been the first one-eyed winger, too. Remarkable achievements on both counts.

Playing left wing, as he did, forced him to turn his head over his right shoulder to see a pass clearly. In 1963, however, while with the WHL’s Los Angeles Blades, wily coach Alf “The Embalmer” Pike, an off-season mortician who presumably knew something about the human body, sensed something was wrong with O’Ree’s eye. He switched him to right wing. O’Ree began to score like gangbusters. His 38 goals led the league that year, followed by four more 30-goal seasons, including one at the age of 39. One is left to speculate how good Willie O’Ree might have been with 20-20 vision in both eyes.

So not only was O’Ree the first black to play in the NHL, he might have been the first one-eyed winger, too. Remarkable achievements on both counts.

As hockey’s black pioneer, O’Ree is often called the Jackie Robinson of the NHL. It’s a poor comparison. Taking nothing away from O’Ree’s breakthrough, the two situations are miles apart. Whether NHL owners were biased against blacks is an open question, but there was no rigidly defined colour bar as there was in baseball, forcing some of the best players in history to play in the Negro Leagues. Robinson’s signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers caused a sensation. O’Ree’s first NHL game was treated as more of an unusual footnote than anything else.

As hockey’s black pioneer, O’Ree is often called the Jackie Robinson of the NHL. It’s a poor comparison. Taking nothing away from O’Ree’s breakthrough, the two situations are miles apart.

Outside of the Maritimes, from where O’Ree hailed, few black Canadians played hockey. A handful did well in the minor leagues and might have been denied a chance because of their colour, but there were no obvious stars. O’Ree deserves every credit in the world for preserving in the sport he loved from boyhood (“I loved the feel of the wind rushing by as I flew along the ice.”) and making history by making it to “the show.”

“I loved the feel of the wind rushing by as I flew along the ice.”

Back in Toronto, after the game ended, my friend and I streamed out of the Carlton St. Cash Box, as sports writers liked to call it, into the late-evening crowds, and headed to the bustling, grim bus terminal at Bay and Dundas for the return trip to Newmarket. We sat quietly in the darkened bus, as the miles flashed by, tired but happy. It had been a wonderful night. The Leafs won 4-1, with the Big M, Frank Mahovlich, and a young rookie, Dave Keon, among the goal scorers. My hero Johnny Bower was the first star, and I had seen Willie O’Ree.

For more Mickleburgh, please visit the Ex-Press archive or visit Mickleblog.com.

THE EX-PRESS, July 16, 2018

-30-

No Replies to "Willie O’Ree’s Wild Ride into Hockey History"